The peal of a bell echoed out across the fields around Low Evering, muted and low but clear in the night’s stillness. Conroy, walking behind the wagon as it trundled its way out of town, hazarded a look over his shoulder, wondering for a moment if it was a signal or alarm before he remembered that the town clock kept time as the Fae did, starting the day in the middle of the night instead of with the sunrise, and that the start of the new day would naturally come with a chime. The bell had rung every night he’d been here, he supposed, but had gone unnoticed as he slept.

He turned his head back forward, letting his gaze linger for a moment on one of the robed figures that flanked him. This one hadn’t spoken back in the square, and they’d been careful to keep enough away from the light that Conroy still hadn’t seen their face. Conroy thought, based on what little he could see of their shape within the loose robe, that they might be a woman, but he wasn’t sure even of that.

He felt a hand close on his arm, firm but not violent. “Come on, Raine,” said Seamus quietly, from Conroy’s other side, “keep up. We’re almost there.”

Seamus had been one of the ones who had spoken in the square; in fact, he’d been the one who’d fallen on top of Conroy, cursing in surprise as he stumbled. As the others had surrounded him with bronze knives drawn and Griff Mason had identified Conroy, Seamus had untangled himself from Conroy’s cloak and slowly got to his feet.

“Shit, Raine,” he’d said, brushing himself off in the dim light of the shrouded lantern, “what in the world are you doing here? I’d have thought you were well asleep by now.”

“The, the lamp was lit,” Conroy had stuttered. “Outside the window. And then I saw movement outside, and I…”

“You got curious,” Mason had said. “As scholarly types often do.” He’d lowered his knife a little, but the other robed figures hadn’t.

The person holding the lantern had turned their head toward Mason. “We don’t have much time until the night patrol comes through,” he’d said, in a loud whisper, “and the stranger knows you and Seamus. What do we do with him?”

Conroy’s eyes had gone wide, and he’d waved a hand in front of him. “I won’t say anything! You have my word! I don’t even know what you’re doing tonight!”

“But he knows we were doing something,” the man with the lantern had said, to Mason rather than Conroy. “And if they catch him out of bed and decide to pull his pendant and glamour him, he wouldn’t have the practice to resist them. He’s a danger to us if we leave him here alive.” The man turned his head toward Conroy. “I’m sorry, but it’s true.”

Mason had extended an arm in front of the man. “He’d be a bigger danger to us if they found him dead. No.” Mason had looked around for a moment, and then his hood had turned back toward Conroy. “We’ll take him with us. Once we’re there, we can figure out what we need to do.”

The man with the lantern had hesitated for a moment, and then nodded. “Fine. Seamus, get him up. Bind him if he won’t come willingly.”

“I doubt that’ll be necessary,” Seamus had said, pulling Conroy to his feet. “Our Conroy here knows he’s better off with us than with the Justicars, yeah? Even if he’s done nothing wrong?”

Conroy had touched his split lip reflexively, and nodded. “Yeah.”

They’d told him to stick close to the wagon and stay quiet, and then they’d set off out of town. The robed individuals had moved quickly but quietly, and the wheels of the wagon had been wrapped in something that muffled their sound as they rolled across the cobbles and out onto the dirt road; for most of an hour, as they’d wound their way out between the farms and toward the far tree line, the only sound had been the faint creaking of the wagon’s axle and the occasional call of some night bird from out beyond the edges of the Human Granted Territory.

Conroy hurried his pace. “Where are we going?” he asked Seamus, keeping his voice at a whisper.

Seamus glanced at him, and then looked up toward the front of the cart. “Griff?”

Mason, holding one side of the wagon’s yoke, shook his head. “He’ll know soon enough.”

“Aye.” Seamus turned his head back toward Conroy, and Conroy could just make out Seamus’ frowning features in the darkness of his hood. “Sorry. Like I said, we’re almost there.”

They walked in silence for another quarter of an hour or so, nearing the edge of the wide clearing that made up the Human Granted Territory. With the moon dark and the lights of the town extinguished, the night sky seemed awash with stars, painting a broad swath from horizon to horizon that seemed almost bright enough to see by.

As they neared a stand of large, bushy trees, Conroy realized that they hadn’t actually reached the outer edge of the Territory; this grove seemed to be separated off from the rest of the forest, as far as he could tell. From what little he could see in the weak lantern-light, the fields around the stand had been left to go to seed, the grass grown waist-high and heavy with thistles and bushes of Atlish broom. The brush in below the trees seemed even more dense, a wall of dark foliage, making the whole grove seem almost a single solid thing.

Mason and the other one pulling the cart turned and left the road, heading straight for the stand of trees across a dead patch in the grass. Conroy expected them to have to turn aside once they reached the wall of brush, but as they drew near Seamus left his side to run up ahead of the cart, grabbing a long stave from the wagon’s side as he went. He disappeared into the foliage, and as the wagon reached the tree line a portion of the shrubbery lifted up, creating a hole in the wall of shrubbery just wide and tall enough for the wagon to pass through.

Conroy ducked under the leaves and followed the cart into the gap. Inside, under the cover of the trees, he could just make out the shape of Seamus, holding the stave up vertically. Once the other robed figure had come through behind him, Seamus lowered the pole, and the branch he had been pushing up with it sank back down, closing the hole behind them.

A dozen paces or so inside the stand, Mason let the wagon roll to a stop. “All right,” he said, pulling his hood back, “we’re good now. Soft voices, but we should be safe.” He took the lantern from where it hung at the side of the cart and removed the shroud. Conroy looked away, squinting for a few moments as his eyes got used to the light, and when he turned back again Mason was looking at him. The older man gestured to the trees around them. “Welcome to the Ironwood Grove.”

Conroy took a moment to take in the scene around him. It wasn’t only the black of the night that made the trees dark; their bark was almost black, even in the lantern light, and they had long, narrow, waxy-looking leaves that were a dull, rusty red. Conroy caught the scent of metal as he inhaled, combined with an unfamiliar herbal aroma.

“I…” He blinked, looking back at Mason. “There are trees we call ‘ironwood’ back in Euphentis, but they look nothing like these.”

“No,” Mason said, “they wouldn’t. These are a Fae creation, something they came up with during the war.”

“So these pre-date the Armistice?” He approached one of the trunks, touching the bark with his hand, finding the tree slightly warm to the touch.

Behind him, Conroy heard the other man who’d pulled the wagon, the man who’d held the lantern back in the square, clear his throat. “We have a little time, I know, but not all night. We should get to the house.”

Conroy looked back. All of the others had removed their hoods except for the one who’d served as his escort; the two who weren’t Seamus and Mason were a man Conroy hadn’t met but who he recognized as one of the Territory’s farmers, and the young man who’d come to warn them of the Magistrate’s arrival a few days before, whose name was Kester if Conroy remembered correctly.

Mason turned to the still-hooded figure. “It’s all right, Cora. He’ll not be telling anyone.” He looked back over at Conroy. “One way or another.”

He heard the woman scoff. “Well, it certainly doesn’t matter now that you’ve gone and used my name, does it?” She turned back toward the wagon and pulled down her hood. For a moment, she seemed unfamiliar to Conroy, but then he thought he’d seen her come into the Jack and Jester one day, dropping off a bundle of freshly-washed linens and picking up a basket of soiled ones.

She looked at Conroy. “Well, now you know our entire little conspiracy, for all it’ll do you. Sufficiently satisfied your curiosity?”

Conroy opened his mouth, not sure what he was going to say in response, but she was already turning away, walking past the cart and further into the grove. Beside the cart, Seamus winced and frowned at Conroy, and then shrugged and motioned for Conroy to follow.

Conroy fell in beside Seamus. “I know her question wasn’t meant seriously, but if it had been, I’d have to confess that I have more questions now than I had before.”

“Understandable,” Seamus said, “but I doubt you’ll get answers to them tonight. We do have business to be about tonight, and it’ll probably be better for everyone if you don’t speak too much, unless you’re asked.”

“What Mason said to her, is he…” Conroy swallowed. “That is to say, does he intend to… get rid of me?”

Seamus frowned again. “You seem a decent fellow, Raine, and Griff isn’t one to kill a man he doesn’t have to.”

“That… isn’t an answer.”

“I know.” Seamus sighed, and then gestured ahead of them. “Look there, we’ve arrived.”

Conroy looked up. In the trees ahead, covered in creeper vines and overhung by dark branches, he could just make out the shape of a building, a mansion or small manor house, built of the same clay brick as the sheriff’s office back in town. The house was in substantial disrepair; the mortar between the bricks was crumbling, most of the windows, especially on the higher floors, were without glass or shutter, gaping black holes open to the night air, and at one end the house’s roof had collapsed under the weight of a fallen tree.

But, as they approached, Conroy could see that much of the bottom floor was still closed up, and here and there he could see evidence of patched mortar or shutters mended, and, when Mason knocked on the door, it opened a moment later, revealing a wiry-looking middle-aged man in worn-looking clothes.

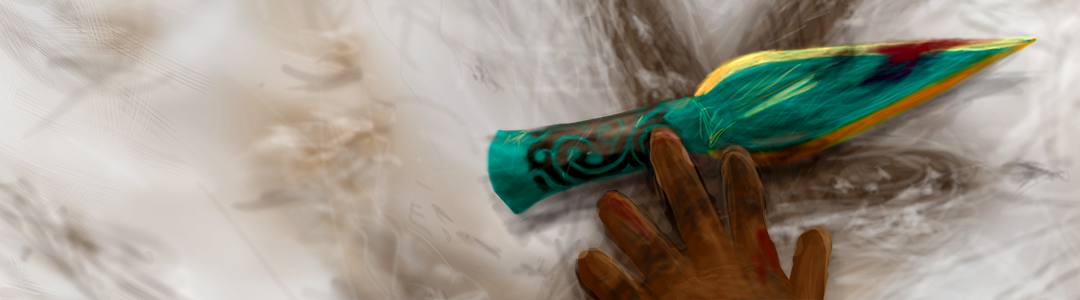

The man had a long knife in his hand, a steel knife, that he lowered almost immediately. “Griff,” he said, in a hoarse, low voice with a heavy Atlish accent. “How goes?”

“Well enough,” Griff responded, “but we have an issue. Do you have enough current saved up to fire up your coil furnace?”

“We should. But why?” He looked around Mason, his eyes settling on Conroy. “A new recruit?”

“That’s up to him.” Mason turned to Conroy. “The men, women and children who live here in this grove have each committed acts that are, under the laws agreed to in the Armistice Charter that created the Human Granted Territory, crimes punishable by long imprisonment, torture or death. Most are no worse than your own crime, your iron ink, the result of unthinking accident or honest mistake. A few of us have decided to help them, bringing supplies and whatever contraband the Sheriff takes that we think might prove useful.

“Most of the people of Low Evering don’t know this place exists; they just know that those who wear the gray hoods collect what alms they can spare and dedicate them to a good cause. The Territorial Authority believes these people dead, caught by us and put down in their name.”

He took a step away from the door, toward Conroy. The woman he’d called Cora jogged forward, stepping around him, and enthusiastically wrapped her arms around the man at the door, a gesture he returned whole-heartedly. The man kissed the woman hard on the mouth, and then they both stood in the doorway, holding each other tightly, as if afraid to let go again.

“So,” Mason said, “now that you know all of this, we have a problem. I like you well enough, Conroy, and my impression is that you’re a man who cares more for human life than for the broken laws the Fae impose on us. I think you can understand and empathize with these people’s plight, and I don’t think that you would willingly betray them. But, as Harald said, you are vulnerable to their glamour, and one suspicious action or sideways glance would be all the justification some Justicar might need to remove that amulet of yours and force you to give up all of our secrets.”

He held up both hands in front of him, as though offering Conroy something in each palm. “So, in the next hour, we can do one of two things. One, we can make you incapable of speaking to anyone ever again.”

“Kill me, you mean,” Conroy said, his throat suddenly dry.

Mason nodded. “I’m afraid so, and dispose of you such that none can find your remains. We can’t be certain any lesser action would work for sure.” He spoke bluntly, matter-of-fact, but there was a hint of apology in his voice.

“Or,” he continued, “two, we can make you immune to glamour.”

“How…” Conroy swallowed. “How would you do that?”

“The same way as it was done to me,” Mason said. “By planting a lodestone in your skull.”

–

Hey folks! If you’re enjoying the story and want to do something small to help out, please vote for Mud and Iron on Top Web Fiction. It takes literally two seconds, and even a single vote can often be enough to put Mud and Iron on the charts, where more people can find and enjoy it. Thanks!